Title: The Gift of the Crystalline Kiss

Author: Peter S. Drang

Genre: Science Fiction

Length: 2200 words (Short Story)

Reading time: About 10 minutes

“This looks like a good spot,” I said, pulling the car under a shady tree and trying to sound cheerful.

Paul glanced nervously at his wristwatch. “Sure, Betsy, a good place . . .”

I knew exactly what he was thinking, what he stopped himself from finishing. A good place to spend eternity. I put my hand on his, squeezed. He looked at me, sighed and mustered a half-hearted smile. I hadn’t seen him happy for seven years, and wasn’t going to now, not just yet.

We got out and I retrieved our picnic basket from the trunk. We walked hand-in-hand through a stand of pine trees, crunching needles under our feet, and once through stood on a high ledge overlooking the mountains. The day was clear and warm and the far away mountains looked still and angular, their frosted peaks contrasting with the looming cliffs of purple and green. The site was awe-inspiring, no matter how often I’d seen it. I smiled at Paul, and for one second I thought he’d forgotten about Planck-this and phase-change-that. Then he glanced at his watch again.

I took a thin blanket from the basket and spread it out, started setting up lunch. I’d brought some fine cheeses—gouda and extra sharp cheddar—table water crackers, a bottle of our favorite Merlot, and some grapes.

Paul swatted at his arm. “Damn!” he said. He scratched at the spot, so hard he started to draw more blood than the bug had. “Damn! Betsy, it burns.”

I stood, rushed over and put my arms around him. “Don’t think about it, sweetie.” He kept rubbing and rubbing. “Just stop fiddling with it,” I said. “It’ll stop hurting long before . . .,” and now it was I who had to stop short.

“How do you know? How do you know it’ll stop? I’m the one who’ll feel it, Betsy, not you.”

I remembered we had a first-aid kit in the car. “Okay, wait, I’ll get something for it.” I ran to the car and thank god the kit actually had some topical analgesic.

When I returned, Paul was standing very close to the edge of the cliff. “What are you doing?” I asked calmly, though my voice caught in my throat.

“It might be better this way,” he said, looking down.

“No!” I said, tears coming to my eyes.

“Death might be better. It would be better for a lot of people, maybe most people.”

He was talking calmly now, too calmly, like he’d accepted it, had made up his mind. I had to pull myself together. Paul would listen to logic, not emotions. I walked over closer to him, looked down. “You could get hung up on those rocks,” I said, speaking quickly. “Then you’d be in pain. Real pain, Paul, not a bug bite. You could still be alive at two-thirty. Do you want that?”

He paused a long time, and I stood there, breathless. Finally, he said, “You’re right, of course,” and he walked slowly over and sat on the blanket.

I sat beside him and applied the ointment to his bite. “See? All better.”

He nodded, looked at his watch again.

I covered it with my hand. “Paul, let’s stop worrying about it. I don’t want it to be like this. Not now.”

“Don’t pretend,” he said. “You’re not so brave. I rolled over in bed last night at half past three, and you weren’t there. You couldn’t sleep. You’re as torn up inside as I am—you just won’t admit it. Put on a happy face, eh? Paint it on while the whole world—the whole universe!—ends.”

I tried to calm down. “I just don’t believe it does any good to think about it.”

“Very nice. Very practical. You’re the practical one, aren’t you? The electronics engineer. Solving practical world problems through engineering.”

“And you’re the worrier,” I replied, getting mad now. “The theoretical physicist. The doomsayer. Well, we’d all be a hell of a lot better off if you’d never figured it out in the first place!”

“Ignorance is bliss, eh?”

“For most of the world right now, it is!”

“That’s not my doing. They wouldn’t let me tell. I tried!”

“The government was right not to let you tell. If you’re right, nothing really matters, does it? And if you’re wrong, then everyone would get upset for nothing.”

“That’s not true! Think of burn victims, Betsy. Or soldiers wounded in the field, women in labor . . . people in intense pain. Think of them.”

“What’s the government supposed to do? Go around putting bullets in their brains today?”

He stared toward the ground, sighed. “Yes,” he said feebly.

“And what about all the happy people in the world?” I said. “What about them. You’d louse up their eternity, wouldn’t you? Like you’ve loused it up for both of us.”

He turned, moved away from me. We sat there for several minutes, brooding.

I crawled over the blanket that lay between us and put my hand on his shoulder. “I love you, Paul. I don’t want to spend whatever time is left fighting.”

He let out a deep breath, nodded, put his hand on mine and patted it. “I’m sorry. I love you too.” He turned to face me, knowing it was time to play our private game. “I love how you always comfort me, and how you always drip syrup on the breakfast table.”

Now it was my turn. “And I love how you always explain things to me, and how you use up all the hot water with your long showers.”

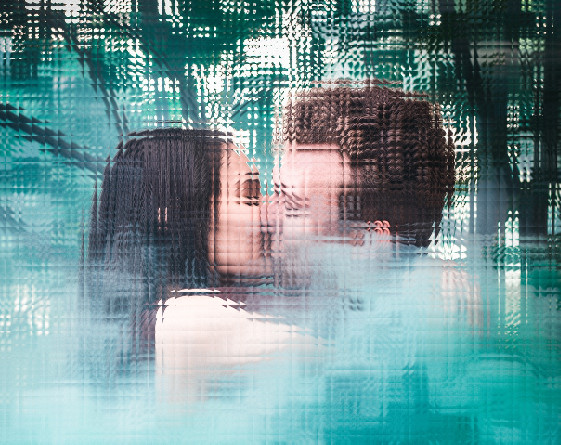

We kissed, and for a moment it was like the past seven years had never happened.

I wished we could stay like that until nine point six three seconds past two-thirty-one pm Mountain Time. The time when Paul figured the Planck “constant” would reach its minimum and space-time would change phases.

“Like water freezing,” Paul had explained to me years ago. “Water stays liquid over a wide temperature range, then around zero centigrade it qualitatively changes—it turns from a liquid into a solid.”

Paul was the one who had figured out about space-time, and how it could also change phases from flowing to frozen if the Planck constant were a low enough value. It was all just a theoretical footnote at first—after all it was Planck’s constant so why should it change? But then some new experiments showed that the Planck’s namesake wasn’t so constant after all and was actually falling in the thirtieth decimal place at an exponentially accelerating pace. It was easy to plug the numbers into Paul’s formulas and project when the phase-change would occur.

Nobody had expected it to be less than a decade away.

More work had confirmed the details of what would happen. The phase-change didn’t completely stop space-time, of course.

“Water molecules still vibrate within ice crystals,” Paul had explained, “they’re just constrained to vibrating between the same neighboring molecules, locked in a crystalline structure.”

The dance of space-time was far more complex than that, he’d said, but something similar would happen. That last instant before the phase-change, that instant would bounce, vibrate, repeat like an old scratched record. That final moment would last forever. Whatever you were feeling at that time—pain or pleasure, joy or sadness, love or hate—you’d feel for all eternity, re-experience it over and over without end.

And there was no chance it would ever thaw. Once time itself had crystallized, the Planck constant would indeed remain constant.

If this kiss between Paul and I had taken place about an hour from now, it would fulfill the desires of every sappy love-song ever written. It would actually be a kiss that lasted forever.

When we parted, Paul wasn’t smiling anymore, and the first thing he did was glance at his watch.

“I’m sorry I built you that thing,” I said. It had been my present to him on our first anniversary, several years before he’d made his grim discovery and a few months after my mom had died. My mom had been diagnosed right after our wedding. Paul was great, staying with me for long hours in her hospital room, never complaining that our first year of marraige was spent that way. So I used my electronics skills to build him that watch, to measure all the hours we’d have in the future.

“I’ve always admired the craftsmanship,” he said, running his finger around the watchface. “Automatically synchronized via radio with the atomic clocks. Accurate to a few microseconds. Marvelous piece of engineering. Your boss never appreciated you like I do.”

“Well, I should hope not.” I said, kissing him again, trying to recapture the mood.

But it was gone.

We nibbled at some cheese, drank some wine. The wine took the edge off, helped loosen Paul up a little, and me as well. We listened to the birds sing, smelled the fresh air, ran our hands along the green grass. We lay down on the blanket and watched the clouds blow slowly by.

“That one looks like a dinosaur,” Paul said, pointing to a long, bumpy cloud.

“And that one looks like the fat woman at the cheese store,” I said.

Paul laughed for the first time in a year. “And look, there’s a cable-car!”

“And there’s a dog with three legs.”

“And that one looks like Big Ben,” he said, and that broke the mood once again. He glanced at his watch. “It’s two-twenty-nine, Betsy.”

“Two minute warning,” I said, trying to smile, but instead my voice cracked and my eyes started to well up.

Why.

Why did I have to know. Be doomed to feelings of infinite loss for all eternity. Paul was right, I was just as broken up about the end of everything as he was. Maybe he had more trouble hiding it because he knew the math better than I, was more certain than I that it all wasn’t just a calculational error. But I came to believe him over the years as he explained it to me, and that was my downfall, my damnation to eternal sorrow. And I’d hated him for it over most of those years. But now, none of that mattered. I loved him now, at the end, and I’d done everything in my power to give him the gift of eternal happiness.

We heard an eagle cry out, and we both jumped to our feet and looked out over the gorge. It flew slowly, in a wide circle. It projected a feeling of confidence, of power, of . . . glory. We watched it until it circled away and disappeared into the trees. It was so beautiful, and now I felt an enormous sense of loss. Everything was over, my job, my friends, the eagle, the whole world. Everything would be gone, except that one, final, everlasting moment.

“Ten seconds,” Paul said, turning to face me. “I do love you, Betsy, now and forever.”

“And I love you, Paul, now and forever.” Tears streamed down both our faces. He kissed me, tenderly wiped away some of the tears, but I could feel the lament flowing in him, coursing through his body, and he started to tremble in my arms.

And then the alarm on his watch sounded.

And a few seconds went by.

And a few more.

“Hey,” he said, our lips still touching. We separated. “Hey!” He looked at his watch. “It didn’t happen!” He waited a few more seconds. “It’s far, far too long, even accounting for supercooling. If it hasn’t happened by now, it won’t!”

We embraced again. But this embrace was different, for he was a different man—strong, resilient—as if his very soul had been frozen all these years and had now itself experienced a phase-change.

“You’ll be a laughing stock!” I said, as we jumped up and down and swung around in circles, giggling like children.

“Well, if I had to be wrong about something—” and he kissed me again, long and hard, and the joyousness of his youth had returned to him, life pulsated through him and through me, too.

He started to say something but I stopped him, kissed him again, pulled him to the ground, held him tight. I wanted this kiss to last forever—not the weak, defeated kiss of a moment ago.

And it would last forever.

I’d made sure of that.

For this was my gift to him: I’d stayed up late last night, not with insomnia, but rewiring his watch to display one minute ahead of the satellite signal’s time. And I’d reset all our clocks while he took his long, hot shower this morning, so he wouldn’t notice.

As the fine-grained lattice of space-time froze around and within us, I thought of how happy he was now—and how happy we both would be, forever and . . . forever and . . . forever and . . .

[END]

Copyright © 2004 Vorpal Publishing Group.